-

Welcome To

Welcome To

Yecla

Yecla

Welcome To

Welcome To

Yecla

Yecla

Welcome To

Welcome To

Yecla

Yecla

Welcome To

Welcome To

Yecla

Yecla

Welcome To

Welcome To

Yecla

Yecla

The history of Yecla is a long and complex one, with historians still struggling to fill in the many gaps in a story of which long parts are missing due to a lack of documentation, but there are certain threads which make it possible to deduce how the town developed during these periods.

These threads consist of the strategically advantageous location of Yecla on the routes which connected the cities and kingdoms of Valencia, Albacete and Murcia, and the types of agriculture which have characterized the local economy for centuries. First and foremost among these, of course, are the grapes which are used for wine production, and nowadays, despite the presence of significant crops of olives, almonds and cereals, after a long and eventful history it is primarily as a Denominación de Origen wine producing area (and for its furniture industry) that the name of Yecla is known in Spain and in the rest of the world.

Pre-history in Yecla

The first known human habitation of the area now included in the municipality of Yecla dates from the late Paleolithic, around 30,000 years ago, and is attested to by the archeological sites at El Madroño and La Fuente. At that time the inhabitants made flint tools such as axes and knives, with which they carved out other items from stone, and various examples of these implements have been found.

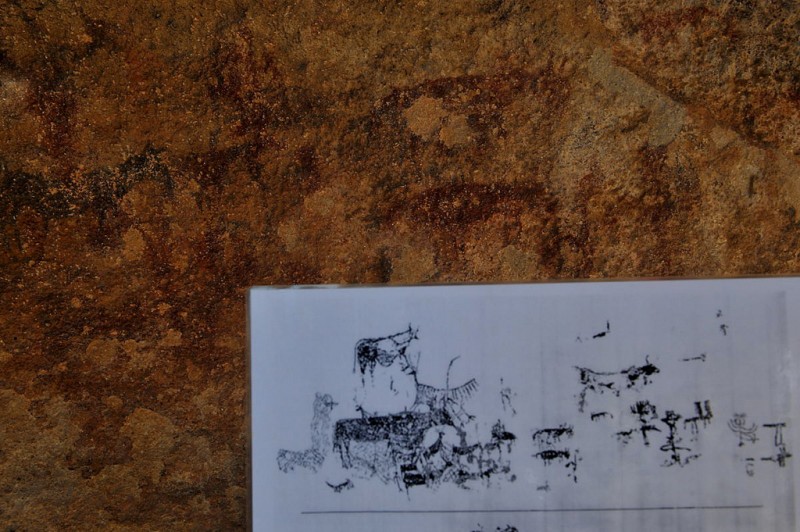

However, by the time the Neolithic period began, in the eighth millennium BC, human society had evolved from a hunter-gatherer existence to the formation of settlements in which cattle were tended and crops were grown. These communities used more advanced technology to produce polished stone and crude ceramics, and the creation of primitive art in caves was also common: in Yecla examples of this can be seen at various locations on the mountain of Monte Arabí. The most important include those of the “Cantos de la Visera”, which were the first examples of prehistoric cave paintings to be discovered in the Region of Murcia and are among those which led Unesco to declare the primitive art of the Mediterranean coastal areas of Spain an Item of World Heritage in 1998.

The archaeological findings made in Yecla continue to illustrate the development of Mankind in the Iberian Peninsula in the third millennium BC. This was the age when metallurgy was first discovered and at the same time the small settlements of the Neolithic gave way to larger conurbations such as those which have been found on the flat land of La Ceja and La Balsa. At both of these sites numerous items of decorated ceramics have been found, while in the burial caves of Sierra del Cuchillo and La Atalaya insights have been gained into prehistoric funeral rites: the grave goods unearthed include axes, glass beads and other trinkets and, once again, ceramics.

As the age of metallurgy transformed into the Bronze Age, in the second millennium BC, so the nature of archaeological findings in Yecla changes once again, with the main site in the municipality from this period being that of the Cerro de la Campana. The inhabitants of this site were living between the Argaric culture, which is believed to have originated in what is now Almería, the inhabitants of La Mancha and the peoples of the Mediterranean coast, and this is reflected in the items found at this complex.

The settlement consists of three distinct areas, with the residential zone located on the hill itself, the hunting and pasture land on the lower slopes and the crop fields on the flat plain below. It is clear that the climate and geographical features of the area around Yecla were conducive to the growth of this kind of micro-society, and other sites where similar populations are known to have existed include those of Arabilejo, Castellar and Pulpillo (all of which them on fortified hilltops), La Perdiz, Monte Felipe, Las Moratillas and El Portichuelo.

By the 7th century BC the Iberian culture had arrived in the Altiplano area of what is now the Region of Murcia, with the south-eastern part of the Iberian Peninsula being occupied by different populations roughly corresponding to Alicante, Albacete and Murcia. Once again Yecla lay in the middle of the three, and the population here lived in huts on the hilltops and left an archaeological heritage rich in pottery and ceramics.

The designs on these items were heavily influenced by the Greeks and the Phoenicians, as is logical given the continuous trading contacts established by those two civilizations throughout the Mediterranean, and in Yecla there is an Iberian burial site on the south-western side of the Cerro de Castillo, the hill on which the castle stood. This site contains various objects which were the subject of religious veneration, including plates decorated with geometrical motifs.

The Romans in Yecla

There was no major Roman town or city on the site of modern-day Yecla but the area continued to be on one of the major routes between the Mediterranean coast, the central plains of the Iberian Peninsula and Andalucía, all of which were connected by the Via Augusta road. This can still be seen today, running through vineyards owned by the Bodegas Familia Castaño.

Yecla, like much of the rest of northern and north-western Murcia, was important to the Romans for its agricultural potential, and archaeological evidence of this has been found in the form of several Roman villas which served to oversee and administer agricultural production. One of these was found quite by chance very close to the centre of the modern-day town, and contained an extremely well preserved mosaic which is now on display in the Cayetano de Mergelina archaeological museum in Yecla.

Wine had first come to Yecla with the Phoenician traders centuries before the Romans occupied Hispania, but the first evidence of production in the Altiplano has been found at Fuente del Pinar, where equipment has been found dating from the 1st to the 3rd century AD.

Other discoveries in Yecla include nine Roman coins (which helped to date the villa of Los Torrejones to around the end of the 2nd century AD) and a bronze amulet containing a figure of Priapus found at the “Casa de las Cebollas”, which appears to show that the native Iberians of the Altiplano were happy to adopt the Romans’ gods and other deities.

Roman burial and cremation sites have also been found in the municipality of Yecla, including those of Las Casas de Almansa and Pulpillo.

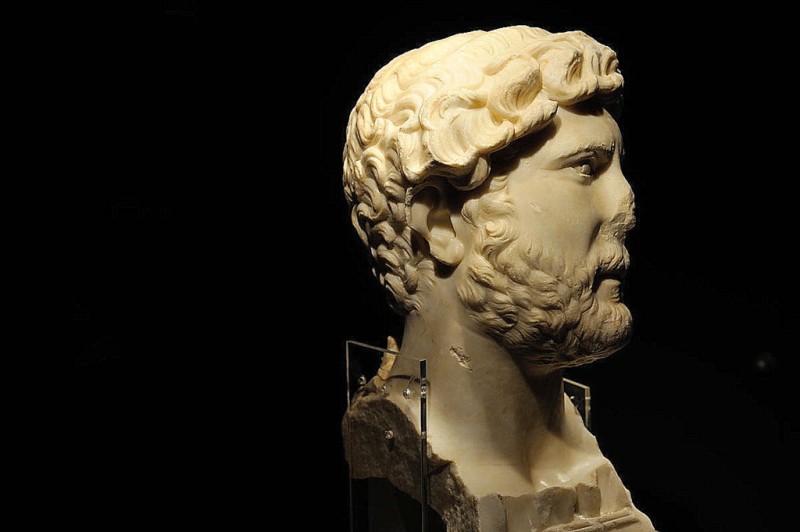

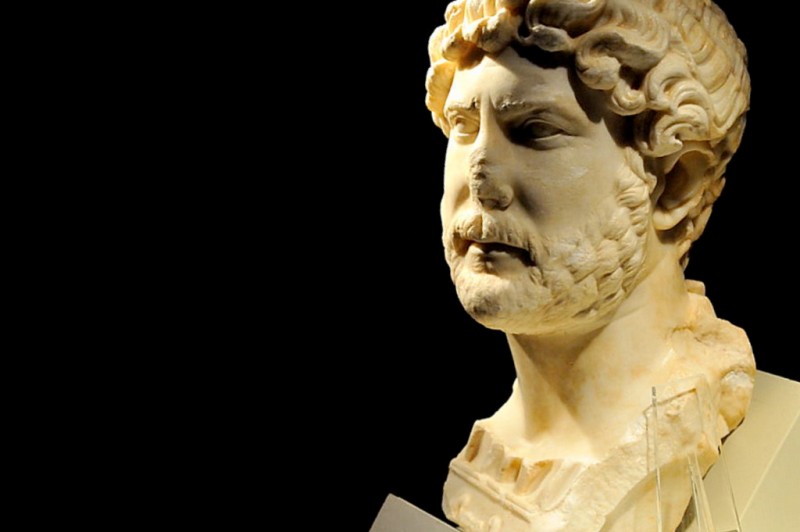

However, by far the most important Roman artefact found in the municipality is a bust of the Emperor Hadrian (full name Publius Aelius Hadrianus Augustus), best known in the UK for the Wall he built in Northumbria and Cumbria to keep out the Scottish “Barbarians”. Hadrian was Emperor of Rome from 117 to 138 AD, and was born in what is now the province of Sevilla in Spain.

The 52-centimetre-high figure discovered in Yecla is believed to date from the year 135, and shows the Emperor with a beard, curly hair set in waves and his head tilted slightly to the left.

It is possible that Hadrian had some connection with the owners of the villa and may have even stayed there on a journey through Spain, giving the bust as a gift. Busts of Hadrian are very rare and the only similar pieces known to exist are in collections owned by the British Museum, the Prado in Madrid, the Museum of Israel and the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

The Moors in Yecla

The fortunes of the Romans in the Iberian Peninsula declined from the 4th century AD onwards, partly as a consequence of the expansion of the Moslem Empire in northern Africa, and in 711 the Moors invaded southern Spain. This led to a rapid depopulation of the area, which for almost 200 years until the 10th century was abandoned, and this certainly appears to have been the case in Yecla, where only a couple of minor findings confirm that there was any human habitation at all.

In the late 10th and the 11th century, though, the Spanish “Dark Ages” began to come to an end, and once again Yecla mirrors the wider picture with the construction of a fortress on the southern side of the Cerro del Castillo dating from the period when this area belonged to the Taifa (or emirate) of Denia. It was at this point that the name of “Yakka” (later Yecla) was coined, in reference not to a town (“medina”) but to the “Hisn”, or castle.

Around the fortress, though, a “medina” soon developed as those involved in agriculture clustered around it for protection, and when the different emirates were united under the Almohad caliphate in the 12th century this acted as a catalyst for further urban development. The advantageous geographical location was again an important factor as the town became one of the most important in the Cora of Tudmir, and significant agricultural concerns grew at the sites previously used by the Romans at Los Torrejones, El Peñón and El Pulpillo. These all feature springs, making irrigation possible to a limited degree.

The Moorish town of Yakka was typical of its age, featuring a maze of narrow streets and houses with interior patios or courtyards, and eventually the fortress was extended in order to provide more protection for the growing settlement. The houses were built on terraces which had to be created on the mountainside, in an area which was protected from cold northerly winds in winter.

Drainage was simple: it was based on gravity carrying rainwater and waste water down the hill, while drinking water came from storage deposits wells which were replenished regularly.

Unlike the first two centuries of Moorish occupation, the 12th and 13th centuries have yielded numerous archaeological treasures in Yecla, and many of them are now on display at the municipal archaeological museum.

The Reconquista and the Middle Ages

The advancing Christian forces of the Reconquista, under the leadership of Prince Alfonso of Castilla, later to become King Alfonso X “El Sabio”, reached the Taifa of Murcia, including Yecla, in 1243, and took power by the treaties of Alcaraz and Almirza.

This was followed in Yecla by the emergence of a new urban area, this time on the northern side of the hill behind the town, where modern-day Yecla stands, and as the Christians gradually repopulated the area the medieval town extended from the Cruz de Piedra to the Cerro del Peñón. By the mid-15th century there were approximately 1,500 inhabitants and the town continued to be owned by the Marquises of Villena until the year 1746.

One of the consequences of the Reconquista was that wine production re-started, having been abandoned during the occupation by the Moors. The Moslems had maintained the vineyards but only in order to harvest the grapes rather than for the creation of alcoholic beverages: however, by the 16th century there is documented evidence in the chronicles of Felipe II that Yecla was already considered a major source of wine.

During this century Yecla experienced a kind of golden age, and again archaeologists have found numerous items dating from the period including ceramics and coins. It was at this time that the project began to build what is now known as the Iglesia Vieja, the parish church dedicated to the Asunción.

But if the 16th century was a time of prosperity, the following one, as was the case in almost all of Europe, was very different. Economic crises hit Spain as the feudal organization of society at last began to crumble, and poor harvests and disease decimated the population.

Yecla, sadly, was no exception, and the fall in population due to disease and famine was exacerbated by the expulsion of the “Moriscos” (the Moors who had chosen to remain in Spain after 1492 and convert to Catholicism rather than be expelled) from Murcia between 1610 and 1613.

But the 18th century marked an upturn in the town’s fortunes, and this is reflected in its rapid population growth: in 1755 the town had already expanded significantly and had a population of 6,608, and by 1770 the figure was close to 10,000 as Yecla expanded northwards.

The plains were largely cleared of trees so that more crops could be grown in the fertile soil, and the town finally began to spread out on the flatter land towards the north. At the same time, the homes of the wealthiest residents (complete with their coats of arms) which can still be seen today were built, as was the Iglesia de la Purísima, on which work began in 1775 (although it was not completed until 1868).

The blue and white dome of this Basilica is one of the most instantly recognizable sights associated with Yecla, and another distinctive building from the same period is the Palacio de los Ortega, now home to the archaeological museum and the municipal library as well as performing other functions.

It is believed that approximately a thousand men from Yecla fought in the Napoleonic Wars, and on 19th January 1812 the town was invaded by Napoleon’s troops, raising the list of casualties and fatalities to include civilians. The events of their occupation are still commemorated in the annual Fiestas de Los Judas in early May, and although the French were eventually expelled by the Spanish forces led by General Miralles this was not entirely beneficial to Yecla, as stiff reprisals for the towns which had signed the Cádiz Constitution followed on the orders of Fernando VII after the restoration of the monarchy.

As the century progressed Yecla suffered further still from attacks by bandits, and after the Franciscan monks were expelled in 1836 more setbacks arrived in the form of outbreaks of cholera.

It was not until the second half of the 19th century that the town finally enjoyed a period of prosperity, with vineyards and wineries making a significant contribution to the local economy and the teachers of the Piarist religious educating the young. These boom years allowed the Basilica to be completed, and one of the most important events in the history life of Yecla was the visit of King Alfonso XII on 3rd December 1878, when he named it a city.

By 1900 the population had risen to the giddy heights of 19,000, well over half of what it is today, and the miracle of electric light was seen for the first time by the Yeclanos before the turn of the century.

The 20th and 21st centuries

If wine was the driving force behind the expansion of Yecla in the second half of the 19th century, in the first half of the 20th the limelight was stolen by the construction of a railway linking the town with Jumilla, the publication of the first local newspaper (El Eco), the arrival of the cinema, the first motor vehicles and the installation of proper water supply and sewage networks.

At the same time, vineyards continued to increase production and the threat of phylloxera was overcome by the import of new vines from America. At some point in the 1920s an excess of labourers at the vineyards and wineries was solved by the setting up of furniture-making carpentry workshops, and this eventually led to the development of another pillar of the economy of Yecla.

The Civil War from 1936 to 1939 put a halt to the boom of the 1920s and early 1930s, and as was the case throughout Spain various churches and items of religious artwork were lost along with numerous lives.

But by the 1950s and 1960s another spate of prosperity was under way as the fledgling furniture sector matured and became more of a 20th century business proposition than a mere cottage industry. Markets and Trade Fairs were held to promote the furniture being produced, specialized training centres were set up to guarantee quality, and such was the success of these initiatives that nowadays there are over 400 companies reported to be engaged either in furniture making or in ancillary tasks such as upholstery and timber supplies in Yecla.

Yecla, along with Jumilla, may in some ways be something of an outpost of Murcia, but due to wine and furniture production it has become one of the key agricultural and industrial locations for the Region. In addition, in the early years of the 21st century the road network has been upgraded to bring Yecla within an hour’s drive of the regional capital, and at the same time it is still on the main communications routes connecting Murcia, Albacete, Alicante and Valencia.

This location is one of the factors which have lain behind the growth of Yecla at various points in its long history, and in the third millennium after Christ the town is still benefitting from it in ways which could not possibly have been foreseen in the past. Just one example is that one of the world’s leading graphene production companies is based in Yecla: a fine example of the modern world sitting alongside more traditional activities such as viniculture and carpentry, and an illustration of the mix of old and new which characterizes Yecla today.

Click to see more information about visiting Yecla and some of the locations mentioned in this history including the wine bodegas.

Hello, and thank you for choosing CamposolToday.com to publicise your organisation’s info or event.

Camposol Today is a website set up by Murcia Today specifically for residents of the urbanisation in Southwest Murcia, providing news and information on what’s happening in the local area, which is the largest English-speaking expat area in the Region of Murcia.

When submitting text to be included on Camposol Today, please abide by the following guidelines so we can upload your article as swiftly as possible:

Send an email to editor@camposoltoday.com or contact@murciatoday.com

Attach the information in a Word Document or Google Doc

Include all relevant points, including:

Who is the organisation running the event?

Where is it happening?

When?

How much does it cost?

Is it necessary to book beforehand, or can people just show up on the day?

…but try not to exceed 300 words

Also attach a photo to illustrate your article, no more than 100kb